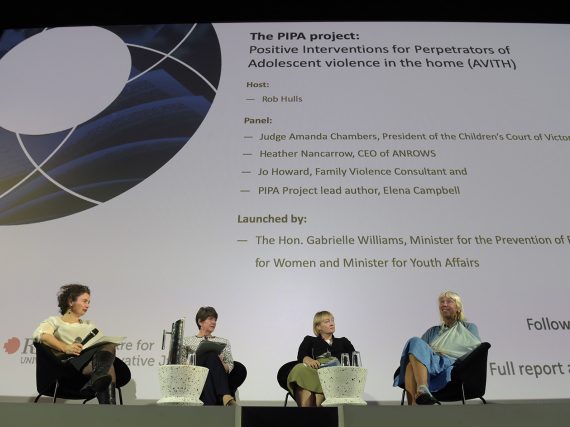

Launch of the PIPA project – Positive Interventions for Perpetrators of Adolescent violence in the home (AVITH)

The launch of the PIPA project on Tuesday 3 March was a chance to reflect on how far we’ve come in the CIJ journey – as well as how much still lies ahead.

After the challenge of AVITH was highlighted in our 2015 report, Opportunities for early intervention: bringing perpetrators of family violence into view, the CIJ decided to focus attention on this under-examined area and, within that, the legal response it receives across three different legislative and policy frameworks. A grant from ANROWS, multiple project partners and considerable work later, it was gratifying to see the interest evident from government, community and legal sectors – and to feel the commitment to reform.

Reform is needed because we found that the legal response to AVITH is a blunt instrument – a one size fits all approach that is often doing more harm than good. The research revealed that we have failed to build nuance into civil mechanisms; discretion into codes of practice; risk assessments into decisions; and evidence about trauma and neurological development into many of the ways in which we work.

For example, while Victoria has opted predominantly for a civil response to family violence, we have assumed that everyone experiencing this response has the same capacity to understand it. Unlike the Personal Safety Intervention Order Act; the Family Violence Protection Act 2008 does not contain any requirement to consider the capacity of respondents to understand or comply with intervention orders, regardless of their age.

This contrasts with the rebuttable presumption at criminal law that children 14 and under do not have the capacity to understand the nature of their behaviour. When recent AIC statistics indicate that 1 in 4 children in contact with police for family violence perpetration are back in police contact within 3 – 4 weeks, including for breaches of intervention orders, it may not be a stretch to suggest that lack of capacity to understand or comply is a factor.

Further, when children are excluded – and in a third of Victorian cases examined this had occurred, at least on an interim basis – the law does not require consideration of the safety of where they are placed beyond whether the adult responsible for them has a criminal record. This sees kids placed with grandmothers, separated fathers, or girlfriends – arguably displacing or dispersing risk, rather than addressing it.

Amongst those children who may be less likely to understand orders, meanwhile, were the kids in 25% of Victorian files who were identified as being on the Autism Spectrum. As we heard across the study, most parents are horrified if their teenage child who has low functioning autism has an intervention order imposed against them – and even excluded – when all the family wanted was much needed support.

Equally, practitioners in the study reported that trauma was almost universal in the clients with whom they worked, with figures released by the Crime Statistics Agency also recently confirming that prior experience of family violence is present in a high number of adolescent perpetrators.

Existing research has long recognised the trajectory of adolescent perpetrators replicating behaviour they’ve witnessed from violent adults in their lives. We have focused far less attention, however, on the relationship of childhood trauma – including intergenerational trauma – to the capacity of an adolescent to communicate effectively or regulate behaviour, or to trust another adult with whom they’re expected to engage.

This is especially relevant in the context of perpetration across generations, or when children are experiencing current abuse – the ‘silent’ or invisible victims of family violence who become all too visible when they start to use violence themselves.

All of this means that the current legal response to AVITH may be criminalising children who are unable to understand or comply with orders; or making them the target of the system’s intervention when they need support and safety, in addition to the support the safety needed by their family.

The good news is that we know how we can do things better. Further, it won’t take an entire upending of the system to make this happen. The PIPA team have recommended specific and quite pragmatic changes to ensure that we respond to AVITH more effectively – and potentially prevent it as well – and it was encouraging to hear support for these recommendations at our launch, as well as from many stakeholders since.

As reformers all over the world – and feminist reformers in particular – are ruefully discovering, it’s not enough just to have a strong, proactive, zero tolerance response to gendered violence and assume that our aim has been achieved. The PIPA project was further proof that we have an obligation to continue to build evidence; to interrogate the mechanisms of the law; and to do so with the safety of those experiencing gendered violence always in our sights.

Elena Campbell will continue to share the findings of the PIPA report across Victoria, including at Monash Law School and at a symposium run by the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare on Friday 13 March; and is planning to attend the ANROWS National Conference in Adelaide in April; and at events in Tasmania and Western Australia later in the year.