New York Study Tour 2019 Blog

The latest from our inaugural New York Innovative Justice Study Tour!

Every year the Centre for Innovative Justice leads a study tour for RMIT Juris Doctor students to see first hand how alternative forms of justice work by visiting specialist courts and having opportunities to meet and hear directly from the people involved. In previous years we have taken the tour to New Zealand and Melbourne, but this year for the first time we are travelling to New York, where many experts and world-leading examples of innovative justice can be found. The CIJ and RMIT students have been hosted by New York’s Center for Court Innovation, which helped us put this tour together.

The 2019 @InnovateJustice @RMITLaw Study Tour to New York is about to begin! Here are our intrepid tour leaders @HullsRob & Student Program Manager Kate Ottrey en route to the Big Apple. Use #NYStudyTour2019 to follow the week's adventures! @RMITLSS pic.twitter.com/vtFPwM9GLs

— CIJ (@InnovateJustice) June 23, 2019

You can download a redacted version of our tour itinerary here: Innovative Justice Study Tour Itinerary (redacted)

The tour begins!

Welcome dinner! @RMITLaw @RMITLSS #NYStudyTour2019 pic.twitter.com/otrC7y7CaA

— CIJ (@InnovateJustice) June 24, 2019

- Kate Ottrey and Rob Hulls at the tour Welcome Dinner in downtown Manhattan

- Students Heidi and Alex

- Students Alyssa and Tara

- Students Dan and Shefton

- Students Dee and Martha

- Students Bronwen and Megan

Day #1 – Monday 24 June

- Observations at the Manhattan Criminal Court

- An introduction to the Center for Court Innovation

- Screening of the documentary film After Rikers and a Q&A discussion with a panel of experts

Great to be with the New York Innovative Justice Study Tour crew outside the New York Criminal Court. We’re off and running! pic.twitter.com/60jKrEu38R

— Rob Hulls (@HullsRob) June 24, 2019

Our Study Tour commenced Monday morning at the Manhattan Criminal Court. As we were arriving we observed the numerous bail bonds offices which lined the street surrounding the court.

The first court we visited was a mainstream arraignment court, which is where a defendant must be brought within 24 hours of arrest. The atmosphere as chaotic, the cases moved quickly and it seemed that no one other than the court staff or legal practitioners had any idea what was going on.

There was an excellent project which had improved court signage within the courthouse so it was much easier to find where you needed to go than in a Victorian Magistrates’ Court, which was great to see. The signage also extended into one of the courtrooms, where there was a plain English explanation on the back of the seats as to who everyone was in the courtroom and what defendants should do when they arrived.

We spoke to two different Judges, a prosecutor (ADA) and a public defender. Each of them spoke about how they were trying to improve the justice system. The prosecutor told us about how they use proceeds of crime confiscated from large scale prosecutions of Wall St banks to reinvest in the police and community programs.

- The Manhattan Criminal Court – “Equal and exact justice to all men of whatever state or persuasion” inscribed on the wall outside

- Manhattan Detention Complex

- There are many Bail Bond businesses in the neighbourhood surrounding the Manhattan Criminal Court

- Students inside the Manhattan Criminal Court where we observed court proceedings

- “In God We Trust” plaque inside the Manhattan Criminal Court

- The group at Hemmerdinger Hall Hunter College for the screening of After Rikers and cross-cultural discussion

In the afternoon, we went back to the Center for Court Innovation to hear about the programs they are running, including working with prosecutors to develop trust between communities and the police to help solve homicides.

Later on we moved up to Hunter College for a screening of the film after Rikers. We’d already seen the original film Rikers back in Australia. Following the film many different community stakeholders joined us for an intercultural discussion on closing Rikers and reducing mass incarceration. These people ranged from former parole officers to those with lives experience of Rikers. This was an extremely engaging discussion.

Great to hangout with @BJHolmes_NYC who is leading @CLOSErikers and @CadeemGibbs who is leading some great youth justice initiatives in NY. Such inspiring stuff & wonderful to be able to share our experiences. #NYStudyTour2019 @FutureSocialAU Thanks to @HullsRob @InnovateJustice pic.twitter.com/WE8fEsNC72

— Shefton Parker (@SheftonParker) June 25, 2019

Would somehow consider going back to law school just for this. https://t.co/4gBbjhktYu

— David Mejia-Canales (@dmejiacanales) June 25, 2019

Listen to Justice in the USA, our latest Talking Innovative Justice podcast where we speak to two US experts on the perils of mass incarceration.

Australia is struggling with similar dynamics as us in the 1990s, with some politicians pandering to people's worst fears and driving up incarceration unnecessarily. I hope that good groups like @InnovateJustice can put a stop to it before they go down the same rat hole as us. https://t.co/wZYiJPYhv6

— Vincent Schiraldi (@VinSchiraldi) June 27, 2019

It's time, it's time for us to move away from the medieval mindset of punishment towards a more restorative, rehabilitative and humane approach. #CJreform @courtinnovation @InnovateJustice @VinSchiraldi @homerventers @HullsRob https://t.co/7rPe94Pk0a

— Kathy Morse (@KathyMorse0914) June 27, 2019

Day #2 – Tuesday 25 June

This morning we took two trains and a bus to the Community Justice Center (CJC) at Red Hook, Brooklyn.

Red Hook was developed to challenge the idea that locking people up creates safer communities. Red Hook offers programs and services instead of incarceration. All their programs are also offered to the local community, because they believe that you shouldn’t have to be arrested to access services. The CJC has lead to a 35% reduced use of gaol.

Student Program Manager Kate Ottrey and CIJ Director Rob Hulls out the front of the Red Hook Community Justice Center

- From right to left- Kara Simpliciano, ADA, Brooklyn District Attorney’s Office/ Edgar Davila, Staff Attorney, Legal Aid Society/ Zazu Tauber, Criminal Court Social Worker, Red Hook/ Alex Perkins, Staff Attorney, Brooklyn Defender Services

- Amanda Berman, Project Director at Red Hook

- Coleta Walker, Associate Director, Peacemaking Program at Red Hook and Brett Taylor, Senior Advisor for Problem-Solving Justice at the Center for Court Innovation

We heard about a newer initiative at Red Hook called Peacemaking. Peacemaking is essentially talking things out. It’s a restorative process based on Native American tribal processes to deal with conflicts between family members, neighbours, police and schools. It’s most successful to heal breakdowns in ongoing relationships. If a case comes to peacemaking, the prosecutors do not get a say in the outcome – they have to trust the community. The defendant decides on their own healing steps with help from the rest of the circle.

A few quotes from the speakers:

“Downtown I would never think about hanging out with DAs (District Attorneys)… here we actually talk.”

“I love this place. More courts should be like this.”

“Traditional courts focus on a person’s past; this court focuses on their future.”

We meet with the court staff in the Youth Court, which is located in the old principal’s office (the building was formerly a school). Teenagers facilitate circle hearings or sit as jurors and ask questions of the respondent. The youth jurors decide on restorative sanctions for their peers.

How wonderful to catch up with Judge Alex Calabrese at the Red Hook Community Justice Center in Brooklyn on our Innovative Justice Study Tour. Our students saw first hand how therapeutic approaches turn lives around.@courtinnovation #NYStudyTour2019 pic.twitter.com/K3jUwqMijy

— Rob Hulls (@HullsRob) June 25, 2019

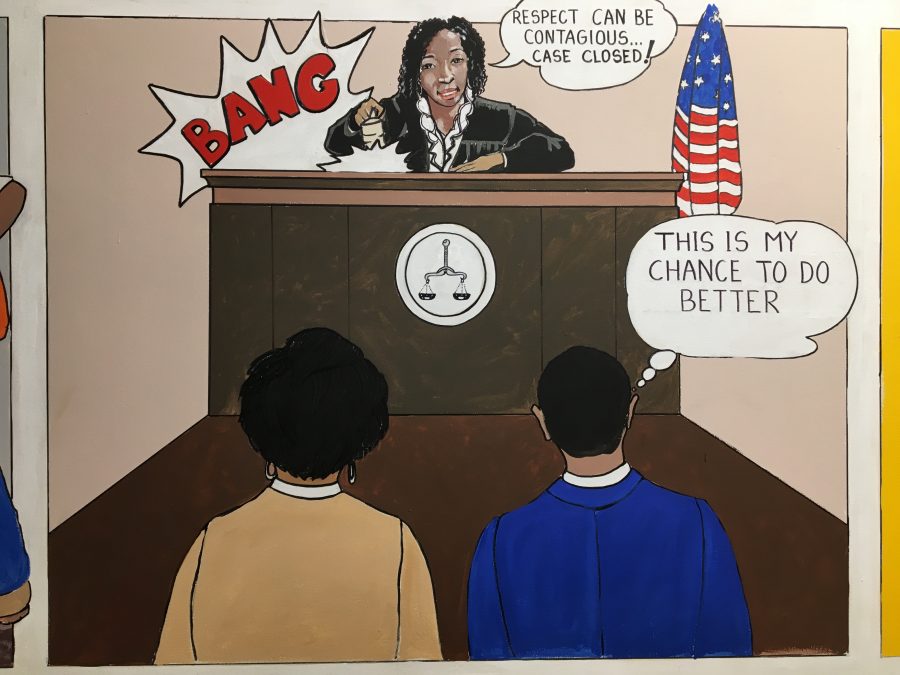

We spent some time observing Judge Alex Calabrese in his courtroom. The mood was totally different to a normal courtroom. It was friendlier. The court officers encouraged members of the public to ask them questions. The Judge spoke to each defendant personally before they left. We all gave a round of applause to one defendant who had successfully completed peacemaking and was having his matter dismissed without a conviction.

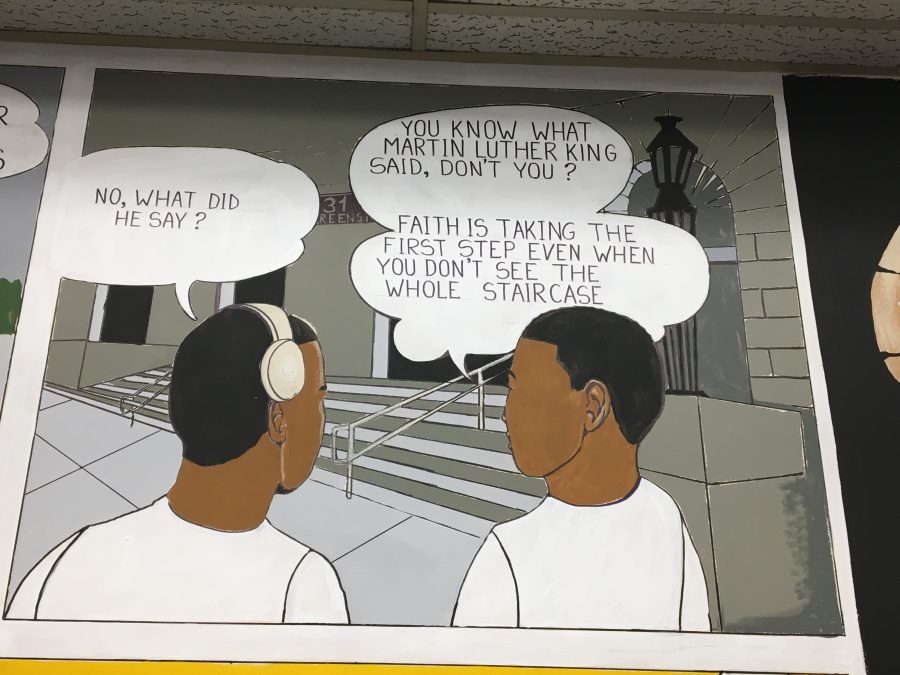

2nd Chance St and Perseverance Road – this mural is on a wall inside the Red Hook Community Justice Center. Pictured is the study tour group with Red Hook and CCI staff.

It was amazing to hear about the wrap around services available to support defendants, but also any other members of the community who walk in the door asking for help.

Had an amazing and inspiring visit to @RedHookJustice today. Thanks to @courtinnovation for hosting (and to @InnovateJustice for letting me hitch a ride on their tour). Incredible work being done to provide fair and just outcomes for vulnerable people. pic.twitter.com/bqkxWcb8m2

— Paul Kidd #BLM (@paulkidd) June 25, 2019

Watch our students Tara and Heidi wrap up the morning at Red Hook:

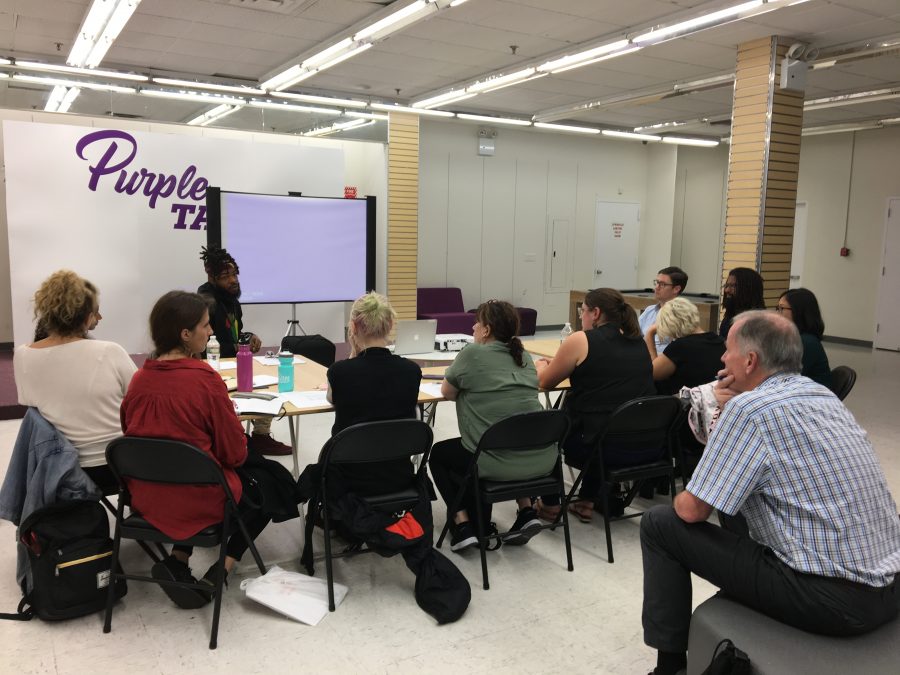

In the afternoon, and with a stomach full of American barbecue, we headed further into Brooklyn to Brownsville. There we heard from the inspiring staff of the Brownsville Community Justice Center.

BCJC is not a court. It is a community centre which organises Dynamic Youth Programs, Place Based Projects (crime prevention through environmental design) and Connecting Residents to Economic Opportunities. They work with young adults aged 16 to 24 years.

Brownsville has 120 000 people in 1.16 square miles. It has the largest concentration of public housing in the USA.

CIJ Director Rob Hulls outside the Bronwnsville Community Justice Center

BCJC engages with the local community. As they put it:

“We’re outside all the time. We are listening; not telling people what we do. We do sight visits and visit parents and young people in their homes.”

Each young person has a “work coach” – similar to a case manager. They attend a civic engagement seminar and connect their personal experience to data. They start asking questions like:

“Does that mean I’m in poverty. How did I get there?”

That is pivotal. It flicks the switch of interest. The conversations lead to young people getting angry and they think:

“What am I going to do about?”

- Deron Johnston, Project Director at Brownsville Community Justice Center presents to the students

- The group at Brownville Community Justice Center

The BCJC offer programs based on the interests of young people, not what staff think they need (for example, basketball group, computer simulation, artistic design).

Social workers attend court to advise the Judge and ADA when they can offer an alternative program for a defendant, rather than gaol or community service. BCJC decided they were having more impact than if they became a court. All their programs are open to any young person, not just those in the justice system.

An example of their work is a group of young people who decided to revitalise a run down park and sports ground. They did the gardening, the weeding, repainted and held a music festival to reopen the park. They designed to flyers and social media. Everything was organised by the young people. Many of the places where the young people choose to undertake a project are places where they have previously felt unsafe and the projects help to reclaim those spaces for the community.

Watch our students Tara and Heidi wrap up the afternoon at Brownsville:

Day #3 Wednesday 26 June

Today we took the NJ Transit to Newark, New Jersey. We visited two different organisations – Newark Community Solutions and Express Newark.

Newark Community Solutions is housed in the Newark courthouse. NSC is a community court within the existing court building and justice system.

NCS has social and community services as an alternative to incarceration or fines. NCS ask community organisations what their needs are and provide clients to them for their community service.

The program is offered by the Judge to the defendant (who Their Honours call a client) pre-plea, with the case left open. If it’s successfully completed, the charge is expunged.

Clients are required to check in with court throughout the process fortnightly. The Judge was engaging, talking to clients, listening to clients. Her Honour set a essay for one client who had failed to attend NCS to answer three questions: Why am I the only person who is responsible for myself? Why I would not do well in gaol? And to reflect on an article she gave him “Forcing black men out of society” from the Sunday Review.

Her Honour led a round of applause for clients who successfully completed the program and asked what they had learned. One client said in court:

“When you ask for help, help is available”.

After court, we visited an NCS victims services centre out in the neighbourhood, working with people who are at high risk of gun violence. People working at the service approach their work by asking people: “what happened to you”, rather than “What did you do?”

All NCS’s work is underpinned by procedural justice:

- Voice

- Understanding

- Neutrality

- Respect

We visited an empty block of land which has been leased from the State for $1 for the year. NCS will use a grant to buy a tool shed and put in garden beds, which community gardeners can use.

Lunchtime at Newark Community Solutions with RMIT students on the Innovative Justice Sudy Tour. Great to see the provision of wrap around services addressing peoples holistic needs.@courtinnovation @InnovateJustice @RMITLSS pic.twitter.com/TIq8qfHdlf

— Rob Hulls (@HullsRob) June 26, 2019

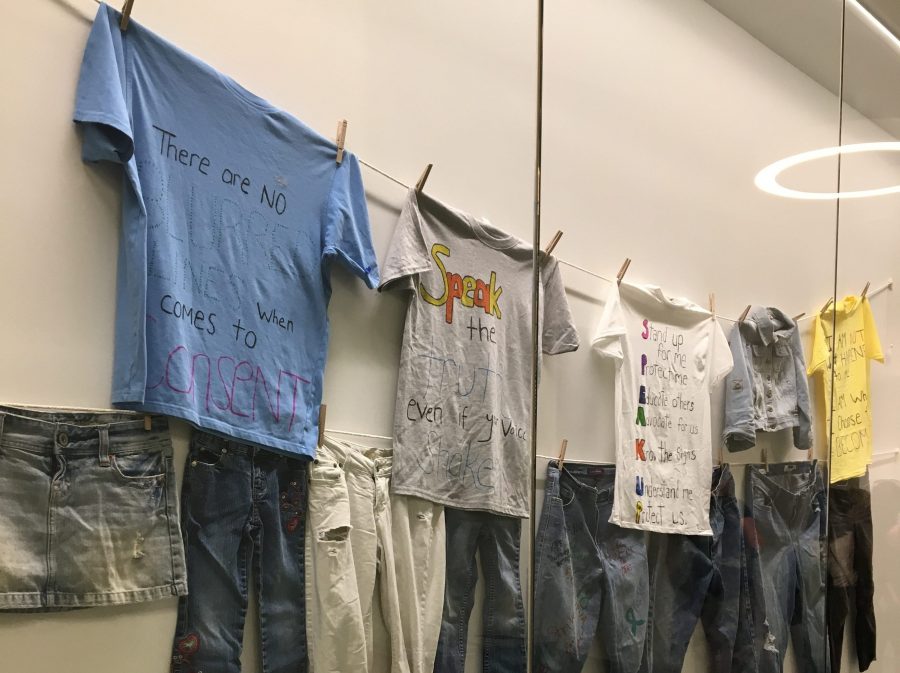

Then we were off to Express Newark, a partnership between Rutgers University and the local community. It provides facilities and teachers for free art classes, photo shoots, film sets, music recording studios, design & 3D printing. They have their own gallery and work with local teenagers in custody or so called half-way houses.

Watch our students Bronwen and Martha wrap up Day #3

Day #4 – Thursday 27 June

This morning we went to the Bronx Hall of Justice to speak to Judge Grasso in chambers and observe the Judicial Diversion and Treatment Court.

Judge Grasso started his career as a police officer before studying law. He was involved in a large scale prosecution of police corruption in Crown Heights.

These experiences taught him to question everything.When he became a Judge, he perceived an extremely chaotic court atmosphere with racially disparate impacts.

Bail bonds were routinely being set for misdemeanours. Even a $500 bail bond is effectively ensuring the demand of a poor defendant.

Not a lot of restorative justice here!! pic.twitter.com/YoQeAWNxsO

— Rob Hulls (@HullsRob) June 27, 2019

Judge Grasso wondered what one person could do. Some days he had up to 209 cases.

Judge Grasso was a member of the behavioural health task force. He told us that you can only effect change by collaborating with people – don’t bring preconceived ideas, bring a philosophy.

The court worked with the CCI to develop supervised release and the overdose avoidance and recovery (OAR) court.

The supervised release program tackles the bail issue. There’s a mandatory needs assessment and it is open to all misdemeanours except domestic violence and non-violent felonies.

This program has reduced the daily Rikers Jail count by 2000 since it started in March 2016. The only way to close Rikers and maintain community safety is through supervised release, according to His Honour.

Judge Grasso is also presiding Judge in the OAR court. It sits on Wednesdays and deals with misdemeanours and non-violent felonies. It relies heavily on procedural justice. The criminal process is kept on hold. If you live a law abiding life and meaningfully engage with program, His Honour will dismiss your case. 68 people have graduated so far.

Later in the morning, we went to Judicial Diversion and Treatment Court, which works with people with mental illness and/or drug addiction. This court deals with felonies after someone has been indicted and includes violent offences. Defendants must plead guilty and agree to participate. The program may not necessarily result in a complete dismissal but a lower penalty. The Judge does not need permission of the DA to divert.

With a tummy full of Jamaican, we crossed the road after lunch to the Bronx Community Solutions.

Bronx Community Solutions works with the mainstream court system. BCS tries to disrupt the current justice system by reducing short term gaol sentences.

They provide interventions as alternatives to gaol, such as community service and social services. BCS run the OAR (overdose avoidance and recovery) court, supervised release, restorative justice circles (Project RESET, Bronx HOPE, Youth Court) and walk-in services. BCS has service providers at OAR court five days a week to assess people on the day they come to court.

The OAR court model has now also been opened at the Manhattan Midtown Court and Staton Island. BCS has resource coordinators in the arraignments court from 9 am until the court closes at 1 am. This is the court where defendants must be brought by police within 24 hours of arrest. They are looking for suitable clients for OAR and supervised release.

BCS also explained to us how supervised release works. The only requirement is reporting. There are four different levels – people on level 1 must report each month and call each month, while at level 4 people must report and call in weekly. The objective is just to ensure defendants appear in court.

Unlike in Victoria, being “street” homeless does not exclude you from being granted supervised release. There is no drug testing or curfews.

They also have a special program of supervised release for 16 to 19 year-olds charged with violent felonies. They have to report a couple of times a week and participate in a program. This is more similar to bail as we understand it in Victoria.

Finally, we observed Judge Soto in the arraignments court. Her Honour and the other staff came and spoke to the students because it was a quiet day. A quiet day is a good day is this court, because it means arrests are down.

Day #5 – Friday 28 June

- Debrief at Center for Court Innovation

- Farewell lunch

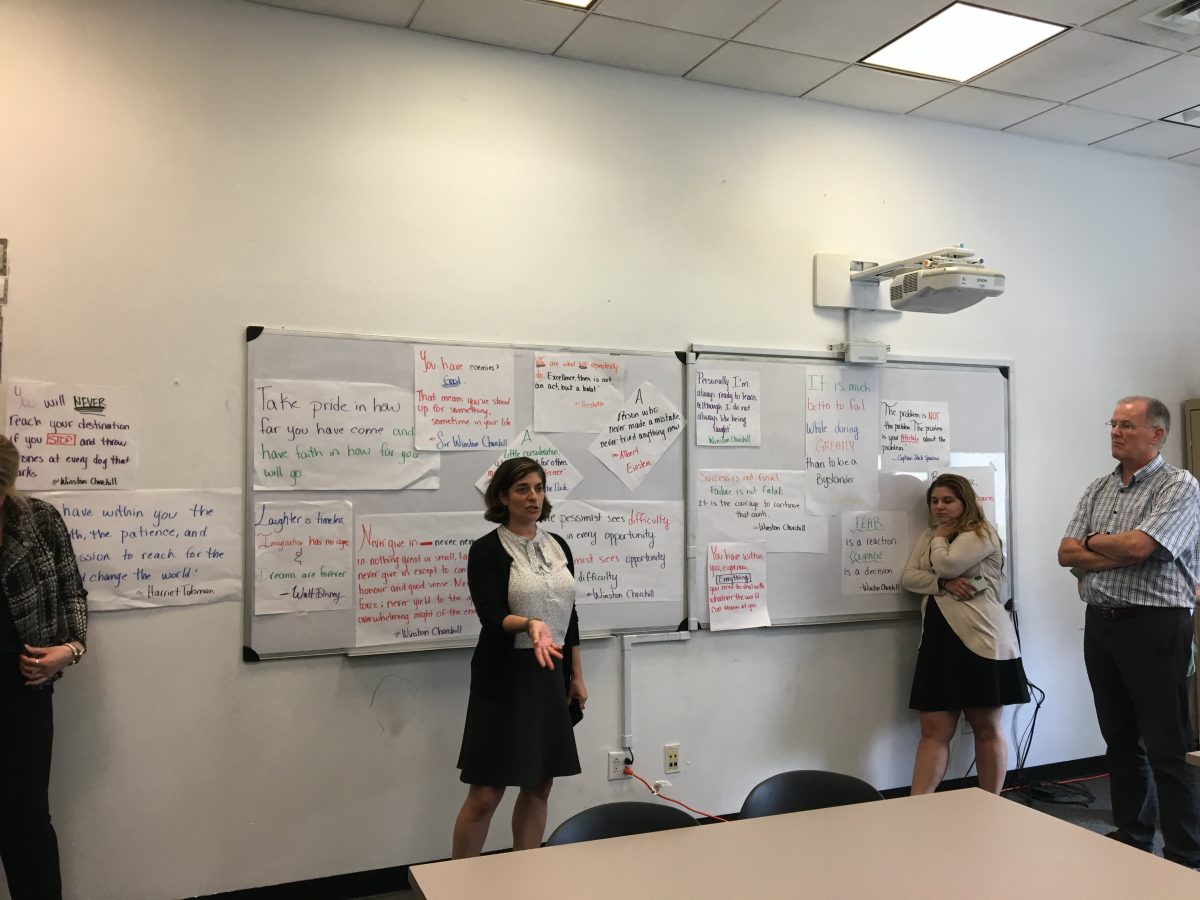

Concluding a very successful New York Study Tour with a debrief at CCI.

We wrapped up the Study Tour on day 5 at the Center for Court Innovation headquarters with a debrief session. The discussion ranged from Victoria’s soaring prison population to illicit drugs to racism.

The mood was sombre, given the enormity of the challenge faced by our own jurisdiction and country, but also hopeful, knowing positive change is possible.

The CCI provided further resources for the students for their ongoing research, such as books and where to find information online.

We ended the tour with a picnic in Central Park. The weather was spectacular, and we enjoyed the ambience, as all around us the city prepared for World Pride on Sunday.

Great way to finish the #NYStudyTour2019. A de-briefing @courtinnovation followed by a bite to eat in Central Park.

What a week! Treating people with dignity and respect & addressing the reasons why they come into contact with the justice system is the key to reducing recidivism. pic.twitter.com/hKbip1zaAk— Rob Hulls (@HullsRob) June 28, 2019

Watch our students Shefton and Megan wrap up the week:

Thanks to our amazing partners at the Center for Court Innovation for sharing their brilliant work with us and to the students for enriching the tour by bringing their exceptional life experience from social services to prisons, public mental health to policing, criminal defence and criminology.

The #nystudytour2019 has been a life-changing experience that has impacted me as a lawyer in training.

In whatever career path I eventually end up in, I will certainly apply these values in any way I can. Thank you so much for the inspiration! @HullsRob @InnovateJustice pic.twitter.com/OqYL5Qpq9m

— Dee Divina (@DivinaThinks) June 28, 2019