Small changes could save the prison system millions and save lives

Criminal justice processes can be alienating and confusing to even the most legally capable of people.

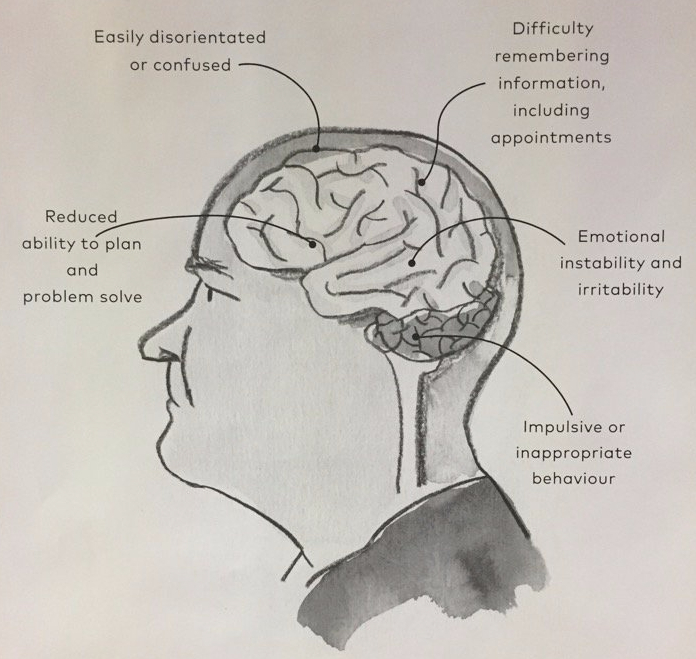

The system must recognise the challenges experiences by a person with an ABI

This article was published on The Age on 25/8/17

Criminal justice processes can be alienating and confusing to even the most legally capable of people. I remember well how confronted I felt when, in Opposition, I appeared in the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal for a Freedom of Information application. I was a lawyer. I was a Member of Parliament. It should have been a walk in the park. Yet the environment and the adversarial nature of the cross-examination process left me somewhat disorientated and disenchanted.

What must it be like, then, for people who have experienced multiple forms of disadvantage throughout their lives? What must it be like for people with an acquired brain injury, people who – for reasons of trauma, comprehension difficulties or simply the multiple forms of disadvantage often associated with ABI – have limited capacity to understand or trust the system into which they have been thrown?

As we acknowledged Brain Injury Awareness Week last week, this is not a peripheral question. Research has shown that around 42 per cent of males and 33 per cent of women in Victoria’s prisons have an ABI. Most are in prison for low-level reoffending – sometimes even for breaches of community corrections orders with which their ABI made it almost impossible to comply. This means that people with an ABI are one of the criminal justice system’s biggest clients. Yet this system has failed to listen, understand or learn from their experience at almost every single point.

The Enabling Justice project, a collaboration between RMIT’s Centre for Innovative Justice and Jesuit Social Services, has been about shining a light on this experience. It has been about deriving lessons from this experience which can ultimately change it. Most importantly, it has been about putting people with an ABI at the centre of the process – not as passive participants, but as advocates for reform – with recommendations based on their own expertise.

These recommendations are not rocket science. Nor are they insurmountable. They are, for the most part, about looking at each point of interaction along the justice system and asking, what if it were different?

In other words, instead of a hostile exchange in which a person’s ABI is not understood or identified, what if an encounter with a Victoria Police officer involved recognition of a person’s ABI, and provision of support so that a police interview occurred with full understanding and effective communication? What if, instead of being physically and verbally intimidated, a woman who has received her ABI as a result of sexual or family violence were treated respectfully by male police officers?

What if, instead of being frightening and confusing, an exchange with a magistrate was an opportunity for someone to feel respected and invested in changing their behaviour? After all, this is what research shows makes the greatest difference to a person’s compliance with an order. What’s more, what if someone were supported by Community Corrections to comply with this order once they’ve received it?

What if someone were assisted in understanding prison processes – including something as simple as turning up on time for medication administration – instead of being left to fend for themselves. What if, upon leaving prison, someone with an ABI (or anyone, for that matter) was supported to find secure housing, instead of being dropped at a bus stop and left with no choice but to sleep under a park bench?