Accessing justice through technology

I have a confession to make. I am not a lawyer.

By Mark Madden, Deputy Director, RMIT Centre for Innovative Justice

I have a confession to make. I am not a lawyer — but have worked with and around lawyers and justice systems for a fair bit of my working life. I have unmet legal need — after being knocked off my bike last year, I am writing off the costs to replace my bike because the time and process required to take the person to a tribunal to get justice makes it simply not worth it.

I am also passionate about building a fairer community and — and I am grateful for those who work in the legal assistance sector and lawyers who do pro bono to help get people justice.

I am sceptical about the ‘innovation’ agenda — sceptical, not cynical — but I am open to the great potential of innovation as a process, particularly in the justice space, and I have been involved in some major technology ‘disasters’, and have learned a few lessons as a result.

Today, I want to start a conversation about innovation and what it means; talk about the potential to deliver greater access to justice and maybe even end the need for pro-bono lawyers; and suggest that the future of law and justice is ‘T-shaped’ or multi-disciplinary and invite you to become involved if you aren’t already.

A basic definition of innovation is a ‘method, idea or product that is new or perceived to be new’. It is important to add ‘perceived’ because sometimes in the innovation space, what was old can be new again! It is important to understand that innovation is a process — and that the quality of the process will be a key factor in the success of the innovation.

We often think of innovation as a product or a piece of ‘hard technology’, usually IT, rather than a new idea or new way of doing or looking at things. We also often think of technology in terms of products, apps for example, when ‘technology’ can be a process. Indeed, at the Centre, our approach to innovation is informed by a method or process, or ‘soft technology’, called ‘human-centred’ or ‘impact-centred’ design, which puts the needs of users at the centre of the process.

What is it that they need, whether as victim or perpetrator, as applicant and respondent or simply someone who just wants an issue resolved, even before its gets into the formal system? Restorative justice, for example, is a method or process or ‘soft-technology’, as is therapeutic jurisprudence and multi-disciplinary practice. It is arguable that ‘adversarial justice’ is ‘old technology’, unsuited to many areas of justice including sexual assault.

This ‘user-centred’ approach can deliver new and challenging insights: in the UK a few years ago they took a user-centred approach to produce a digital map of what they thought was their justice system.

A key outcome was that the justice system was not by any definition a system at all.

That was and remains a powerful insight if you are serious about the task of improving or indeed creating a genuine justice system and delivering greater access to justice.

What is innovation: the available technology?

When it comes to ‘hard technology’, however, there is plenty out there that can be and is currently being used in the justice sector, from mobile phones to artificial intelligence and machine learning. If you have a modern mobile phone with a virtual assistant you have both.

Many of you may have heard about ROSS, based on IBM’s Watson artificial intelligence platform, sometimes called the world’s first robot lawyer. Indeed, if you are a user of e-bay, either as a buyer or seller, and have had a dispute, your dispute has essentially been resolved by similar technology. This technology allows e-bay to resolve millions of disputes across the globe every year. You may also be aware of the use of so-called ‘chat-bots’ to help people deal with a range of issues from parking fines to applications for asylum.

However, this technology is only as good as the process of innovation that has influenced its design and deployment.

Access to justice, meeting unmet legal need

My interest in innovation in the justice sector is not driven by the need to make law firms more profitable or predict the likelihood of particular judges making particular decisions in particular cases. It is motivated by the desire to improve access to justice for those who currently have little or no access.

We know from the NSW Law and Justice Foundation Report of 2012 that there is a huge unmet legal demand in Australia; that legal problems are widespread and impact on many other areas of peoples’ lives.

We also know that a sizeable proportion of people take no action to resolve their legal problems and consequently achieve poor outcomes; that most people who seek advice do not consult legal advisers, and if they can resolve their legal problems, they do so outside the justice sector — perhaps, reflecting the comments I regularly hear from lawyers that you should do everything you can to avoid going to court!

We also know the criminal justice sector is under great stress and strain, with growing demand, limited resources and longer waiting times.

In my view, innovative thinking that drives the smart deployment of ‘hard technology’ has the potential to dramatically improve this situation, with some important caveats, which I will come to later.

For example, in civil justice, a report on OnLine Dispute Resolution by HiiL Innovating Justice based in The Hague, suggests that the clever use of ODR makes the promise of 100% access to justice possible. The report says ODR has the potential to solve the internal dilemma of courts (and governments) that goes something like this — if we offer more effective and fair procedures, we will be overburdened with cases for which we have no funds.

A structured and intuitive ODR process can help the vast majority of people resolve their own disputes and be costed in such a way that most litigants can afford the necessary fees, as well as enable greater co-operation between courts and tribunals.

And while it may change the role of lawyers — and indeed potentially make their work more interesting — it won’t necessarily change the need for lawyers, and it opens up a whole new — and affordable — legal services market. Imagine that.

An ODR court is underway in British Columbia, the UK is moving in this direction and the recent Victorian report on Access to Justice canvasses ODR. Digital technology is also already transforming our courts in other ways, which I haven’t gotten time to go into here.

However, this is where my scepticism, and the caveats, comes in.

This ‘hard technology’ has great potential to improve access to justice, but the effects will be limited it we don’t take the opportunity to deploy ‘soft technology’ like human-centred, or ‘impact-centred’ design to see the sector with fresh eyes, seek the views of users and take the opportunity to re-think and potentially re-create a system for the 21st century.

If we don’t do this — as Sir Ernest Ryder (President of Tribunals in England and Wales) has said, we simply risk fossilising old and out-dated processes and practices in a layer of ‘hard technology’.

The existing approach and solutions has the potential to be very expensive and therefore unlikely to be embraced by governments. If we don’t take this opportunity, to rethink and redesign, if the solutions are not scalable and if it outcome is not going to be embraced or responded to by users’ (because they weren’t involved) then it is unlikely to succeed.

So governments, courts and organisations in the justice sector need to take the opportunity to rethink and redesign the delivery of justice — and their own internal systems — from the users’ perspective — from the laws and rules we created to the processes we support and fund — and then decide what solution will deliver better outcomes, which surely must be greater access to justice.

And in doing so, they need to invite new partners from outside, including from the innovation, technology and particularly the design communities — as well as their ‘clients’— to help them and jointly start to think genuinely outside the box.

This process of ‘co-design’ may have to be pro-bono, of course, — at the start!

T-shape justice reform

In short, justice reform needs to be multi-disciplinary, or ‘T-shaped’.

Two years ago, the Centre embarked on the Access to Justice through Technology stream (A2JTC) of RMIT’s Fastrack Innovation Program with the support of Victoria Legal Aid and the Federation of Community Legal Centres.

This is a program where the best and brightest students from across the University are given the opportunity to tackle an access to justice issue. While mentors from the legal assistance sector support the students, there were doubts at the start about whether it would work. And, for good reason. We would be asking undergraduate students in teams of three, with no legal background, to use their design thinking skills and the skills and knowledge from their various disciplines to tackle complex social and legal issues. And to do it in 13 weeks!

This was no theoretical exercise. Their solutions had to be desirable, feasible and viable.

The outcomes were beyond expectation. The mentors were amazed by how quickly the students grasped the issues and just as importantly challenged the way they had thought about the issues.

Two of the projects on family violence were sent for consideration to those implementing the Family Violence Royal Commission and another two, addressing fines and infringements we hope to get to the market, although finding the resources in the sector to do this is another major challenge.

The solutions in the 2016 program were just as impressive with challenges including a solution to end the referral roundabout in the sector but track unmet legal demand in real time, provide legal education and advice in visual form for CALD communities,and helping to prevent young people being exploited at work.

I realised after the first year that we had created what has been referred to as T-shaped justice reform.

That is, the skills and knowledge of the teams combined deep knowledge of an area (represented by the vertical) with cross-disciplinary thinking (represented by the horizontal). I think this is the way of the future, and the lawyers and the organisations who can combine these, either internally or by co-opting and embracing others are also the lawyers and organisations of the future.

Conclusion

This brings me back to an interesting point that emerged during a series of discussions I had last year around design, technology and access to justice and in particular a Dutch online dispute resolution system, called Rechtwijzer.

The system development was informed by design thinking. Despite the fact that it was ‘humanising’ dispute resolution by empowering people to resolve their own disputes — it was in some instances referred to negatively as a ‘robot-law’.

However, as one participant reflected later ‘what could be more robotic than the way we lawyers currently work in a system that for most people does not compute.’

It is an interesting idea that good design coupled with the right ‘hard technology’ could help us bring more of the human element into our justice sector and deliver greater access to justice and indeed create a real system.

It is an idea or innovation worth pursuing, and you can start the journey, by walking a mile in the shoes of your clients or users of the justice sector by asking simple questions, ‘what are your needs? What was your experience?’ You can also think about how much of what you do is administrative and repetitive and takes you away from what you would prefer to be doing.

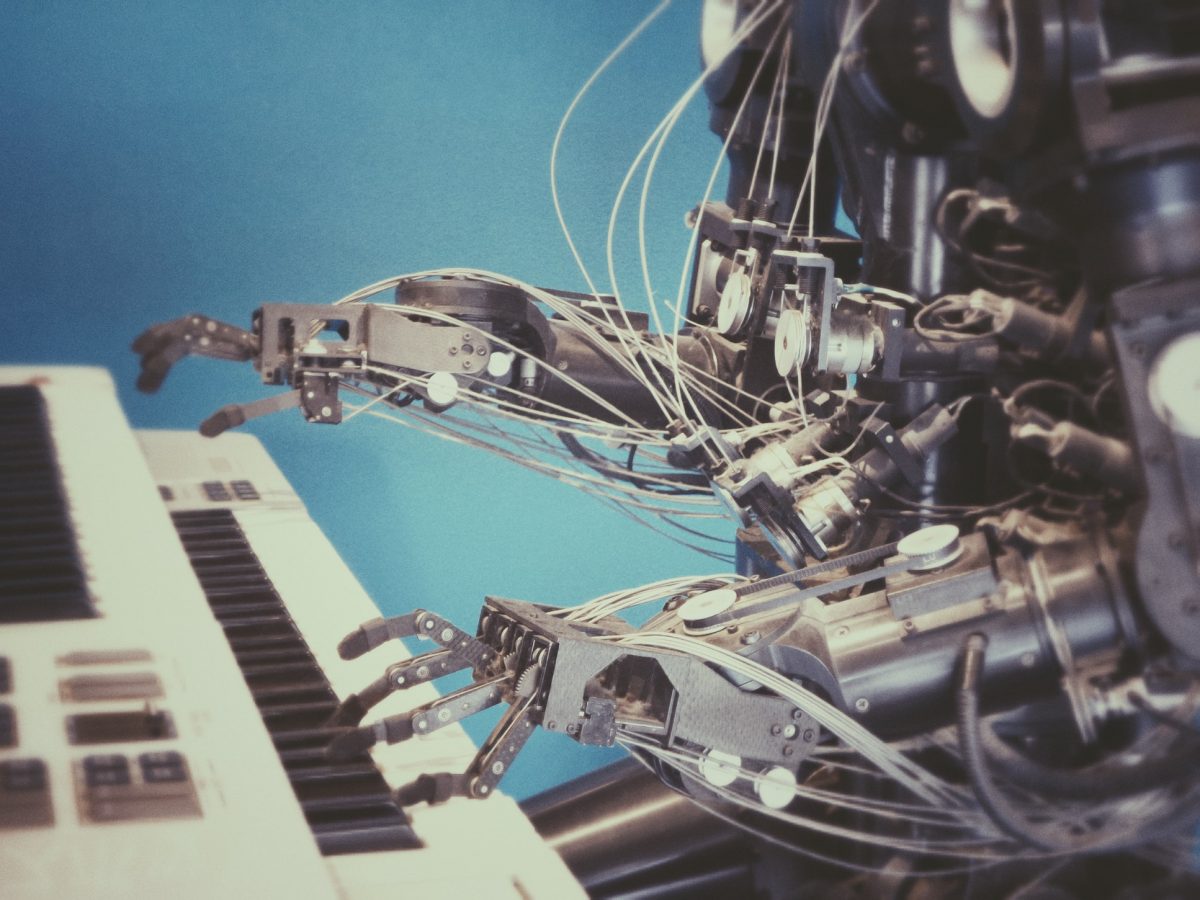

For centuries, justice has resisted or at least failed to embrace change. It has fought to keep pilot programs at the periphery and to insist that this is the way it has always been done. Today, with technological innovations there is real potential to address access to justice as never before. The process is challenging and rewarding but if we don’t take the opportunity to rethink, reshape and innovate, the header image accompanying this blog may be the future we face.